Chapter 13 -- A Social State for the 21st Century

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century (Harvard University Press 2014)

Patrick Toche

Introduction

- This set of slides surveys selected topics from Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a book written by economist Thomas Piketty, published in English in 2014 to great acclaim.

- All source files for this course are available for download by anyone without restrictions at https://github.com/ptoche/piketty

- The full course is expected to be completed by April 2015.

- Chapter 12 examined the dynamics of wealth inequality at the global level.

- Chapter 13 considers political institutions to regulate modern capitalism fairly and efficiently.

Some Questions

- The 20th century wars wiped out much of the wealth accumulated over the previous centuries, and transformed the structure of inequality.

- 70 years of peace have brought hopes and challenges:

1. the end of poverty2. the rise of inequalities

- What political institutions could regulate the accumulation of wealth fairly and efficiently?

- New instruments are needed to regain control over the financial system.

- The social state needs perpetual reforms, to reduce its complexity, to increase its efficiency, to face new challenges.

Financial Crises

- Financial crises disrupt the accumulation of capital and harm everyone.

- The crisis of 2008 was less severe than the Great Depression, because governments and central banks acted to keep the financial system from collapsing.

- Central banks are the only public institution capable of acting as lender of last resort and avert a total collapse of the economy.

- But these actions are surely not a durable response to the structural problems that made the crisis possible.

- A progressive global tax on capital would promote the general interest over private interests while preserving the forces of competition.

Financial Crises

The State in the 20th Century

- Figure 13.1 shows the historical trajectory of the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Sweden, countries that are fairly representative of rich countries.

- Until 1914, total taxes were below 10% of national income.

- States mostly focused on the 'regalian' functions: police, courts, army, foreign affairs, general administration.

- States also financed some infrastructure, schools, hospitals.

- Between 1920 and 1980, social spending as a share of national income rose by a factor of 3 to 4 or even 5 (in the Nordic countries).

- Between 1980 and 2010, the tax share stabilized everywhere.

Regalia

The State in the 20th Century

- Taxes stabilized at different shares of national income in different countries:

- 30% in the United States

- 40% in the United Kingdom

- 45% in Germany

- 50% in France

- 55% in Sweden

- In all rich countries, the share of taxes in national income rose from below 1/10th to over 1/3, and 1/2 in some countries.

Government Social Spending

- The rise in government spending can be broken down into two roughly equal halves:

1. health and education2. transfer payments

- Health and education takes a share of 10–15%, amounting to between 1/2 and 3/4 of total cost.

- Health insurance is public and universal in most of Europe. Obamacare is taking the United States in that general direction.

- Primary and secondary education are free or greatly subsidised in most rich countries, but higher education is expensive in the United States.

Government Social Spending

- Social spending accounts for nearly all of the increase in public spending.

- Replacement incomes (pensions and unemployment compensation) and transfers (family allowances, guaranteed income) take a 10–20% share.

- Pensions account for 65-75% of the total.

- Public pensions have eradicated poverty among the elderly. They are highest in Italy and France (13-15% of national income), lower in the United Kingdom and the United States (6-7% of national income).

- Unemployment insurance takes less than 2%.

- Income support takes less than 1%.

- Total social spending takes 25–35% of national income.

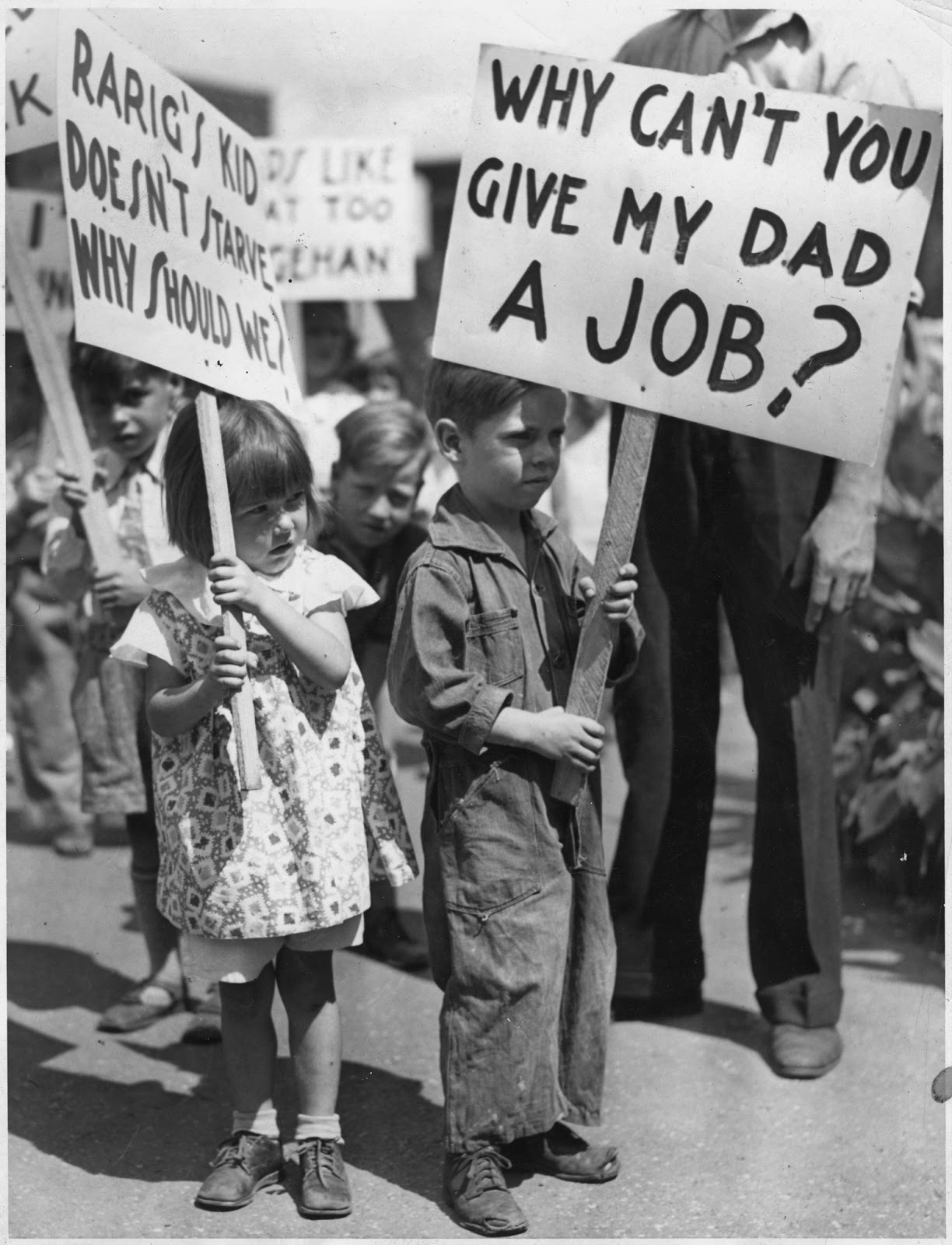

Before Public Pensions

Modern Redistribution

- The modern state does not transfer much income from the rich to the poor directly — but it finances public services and replacement incomes available for everyone.

- The growth of the state was made possible by the high rates of post-war economic growth.

- Since the 1980s, with per capita income growth barely above 1%, there is little support for tax increases.

- The organization of a large state raises efficiency issues.

Education and Social Mobility

- One of the main objectives of public spending in education is to promote social mobility.

- Despite a large rise in the average level of education over the 20th century, earned income inequality has increased. Qualification levels have simply shifted upward.

- The intergenerational correlation of education and earned incomes, which measures the reproduction of the skill hierarchy over time, shows no trend toward greater mobility over the long run.

- Mobility is highest in the Nordic countries, lowest in the US, and intermediate in France, Germany, and the UK.

Upper, Middle, and Lower Classes

Education and Social Mobility

- Belief in high social mobility in the United States is a myth.

- The top US universities charge very high tuition fees. These fees have risen sharply since 1990.

- The proportion of college degrees earned by children whose parents belong to the bottom two quartiles of the income hierarchy stagnated at 10–20% in 1970–2010, but rose from 40% to 80% for children with parents in the top quartile.

- Parents' income is an almost perfect predictor of university access.

- The average income of the parents of Harvard students is currently about \$450,000 — the average income of the top 2% of the US income hierarchy!

The Future of Education

- In Nordic countries, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, tuition fees are usually low (less than €500). Most people believe that access to higher education should be free or nearly free, just as primary and secondary education are.

- There is no easy way to achieve real equality of opportunity in higher education. Parents' incomes are still the best predictor of their child's future income.

- High tuition fees create inequality of opportunities, but they foster the independence and prosperity that make American universities dominate world rankings.

Free Education Protest

The Future of Retirement

- In pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) pension systems, contributions are deducted from the wages of active workers and paid out as benefits to retirees.

- In capitalized pension plans, contributions are invested and the returns used to finance benefit payments.

- Most public pension systems are PAYGO.

- In PAYGO, the rate of return is by definition equal to the growth rate of the economy: contributions rise at the same rate as average wages.

The Future of Retirement

- When PAYGO systems were introduced in the 1950s, growth rates were high — both demographic growth and productivity growth were high.

- Today, the rate of wage growth is lower, but it is also more predictable, while the return on capital is very volatile.

- A transition from a capitalized system to PAYGO would be problematic.

- A difficulty of PAYGO is that different rules apply to different professions. Governments need to establish a unified retirement scheme based on individual accounts with equal rights for everyone.

- What kind of fiscal and social state will emerge in the developing world?

- China is developing a social state similar to Europe and America, financed by a broad-based income tax.

- India has maintained low levels of taxes and a small social state.